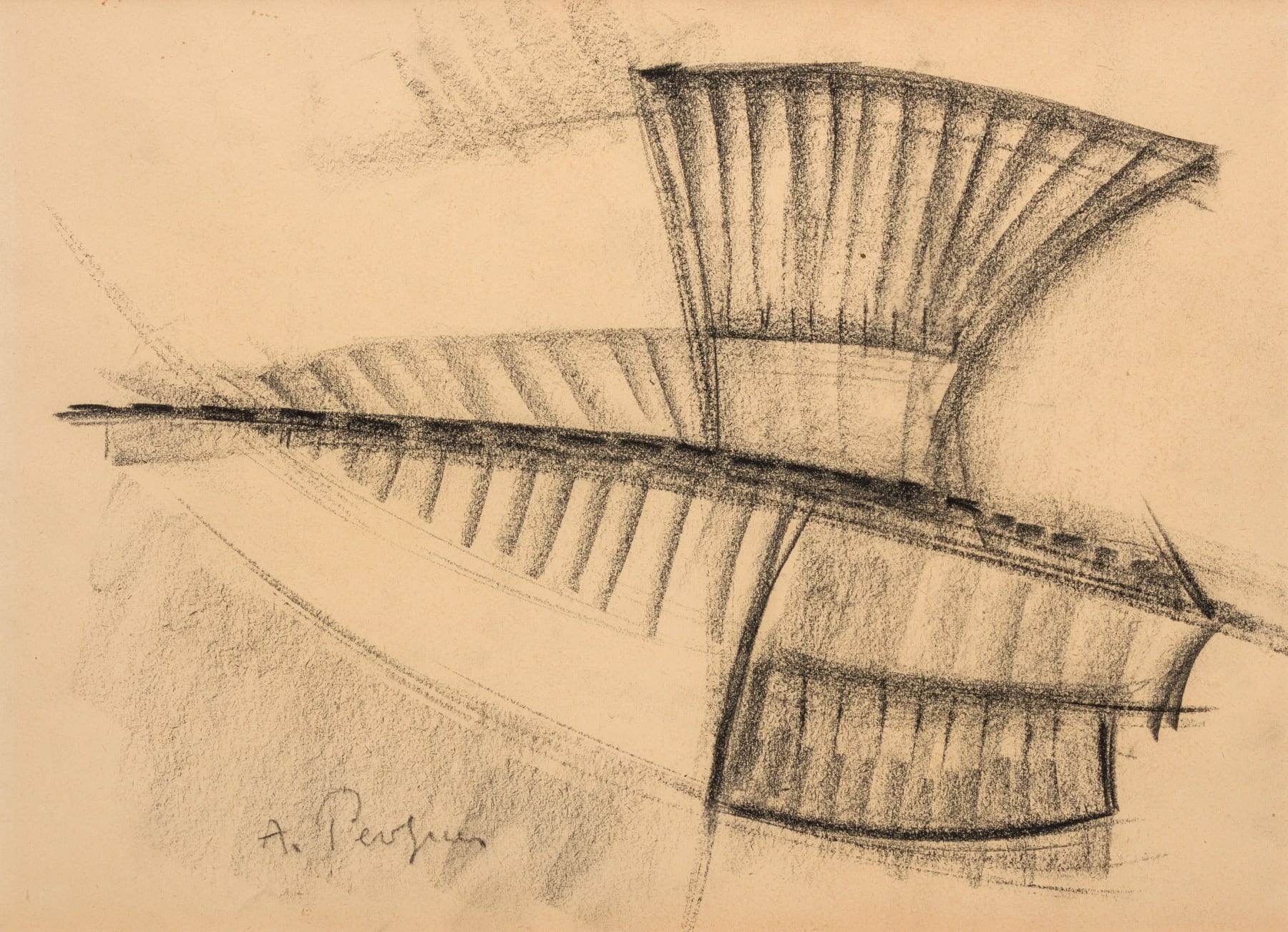

Antoine Pevsner 1886-1962

23.5 x 32.5 cm

Pevsner

was a Russian born sculptor and painter who studied at the School of Fine Arts

in Kiev from 1902-1909 after which briefly attending the Academy of Beaux-Art

in St Petersburg. Moving from painting to sculpture Pevsner initially used

plastic and glass before turning to metals such as copper and bronze,

emphasising the industrial elements of his work. Pevsner’s time studying art

during the first decade of the twentieth century resulted in two pivotal visits

to Paris in 1911 and 1913, at which point he took inspiration from the Cubism

art movement. Generally accepted to have been stimulated by Pablo Picasso’s Les

Demoiselles d’ Avignon (1907), this movement offered Pevsner and his

contemporaries alternative ways to explore perspective that rejected previously

dominant Renaissance trends. Moreover, according to the art historian Douglas

Cooper, Cubism was ‘stylistically the antithesis of Renaissance art’, with

Picasso’s Demoiselles remaining the ‘logical picture to take as the

starting point for Cubism because it marks the birth of a new pictorial idiom’.

Cubism overturned established conventions of perspective by introducing

technical innovations and new types of artistic expression which, Cooper

continues, ‘constitute virtually all the avant-garde developments in

western art between 1909 and 1914…[and] has proved to be probably the most

potent generative force in twentieth-century art’. It was during this same

period, however, with tensions in Europe building and in an atmosphere of

impermanency and flux, that the subsequent sociopolitical, religious,

intellectual and cultural fractures paved the way for abstraction. In an

increasingly mechanised civilisation, Pevsner and his brother Naum Gabo became

part of a small group of experimental engineers, architects and painters who in

1913 united under the banner of anti-naturalism in Moscow. Their new medium was

steel and not paint, whilst composition on traditional forms of canvas was

replaced by construction in space.

Following

the start of the First World War Pevsner sought refuge from serving in the

Russian imperial army by joining his brothers in Norway which, according to

Alexei Pevsner, was when their notion of Constructivism was first conceived. On

the eve of the Russian Revolution in the spring of 1917 the siblings returned

to Russia, at which time Pevsner took up a teaching position at the Moscow

School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. Out of the horrors of World

War One, Pevsner’s brother, Gabo, with whom his artistic influences were

shared, wrote of their inspiration that ‘I am trying to tell the world in this

frustrated time of ours that there is beauty in spite of ugliness and horror. I

am trying to call attention to the balanced, not the chaotic side of life – to

be constructive, not destructive’. Constructivism was an early

twentieth-century art movement founded in around 1915 by Vladimir Tatlin and

Alexander Rodchenko, but was later re-established by Pevsner and Gabo in the

West after the movement was supressed in Russia during the 1920s.

The

foundation of the VKhUTEMAS (Higher state artistic and technical studios) in

1920 brought together three major movements in art and architecture –

Constructivism, Rationalism, and Suprematism – with the intention of

transforming attitudes to art in post-revolutionary Russia. Combining art with

politics, efficiency and production the VKhUTEMAS sought to organize a

curriculum based on contemporary artistic trends and was supported by the

appointment of established master artists. One such artist was Pevsner, who was

awarded a professorship. After years of war and revolution the new Soviet

government were keen to show western Europe their artistic endeavours and in

1922 sent the First Russian Art Exhibition to Berlin with work from both

Pevsner and Gabo included in the exhibition programme. Unfortunately, the

working relationship between artists and institution was not to last. Following

increased pressure from academic and official circles, the focus turned towards

the proletariat resulting in an insistence on ideas centred on utilitarian and

realistic art. Such a return to naturalism was, inevitably, incompatible with

Pevsner’s ever developing artistic expression and professional direction.

Pevsner’s

antipathy to the new objectives meant that it was also in 1920 that he

co-signed Gabo’s Manifeste Réaliste (Realistic Manifesto), which was to become

the key text of Constructivism. Such a bold move brought the brothers into

conflict with the new Russian state. Printed as a handbill the manifesto

addressed five key principles: communicating the

reality of life through space and time; that concepts of space are not limited

to volume; to renounce colour as a pictorial element; to renounce the descriptive

element in a line; and finally that the removal of imitation enables the

discovery of new forms. At its core and thus underpinning these principles was

that kinetic and dynamic elements expressed the real nature of time because

static rhythms were insufficient. Whilst Constructivism is

associated with the structure of the physical universe with intellectual roots

derived from modern physics, what artists present to their audience has not

been seen as solely scientific but also poetic. Indeed, according to the

English art historian, poet and literary critic Herbert Read, Constructivists

art is the poetry of space, of time, of universal harmony, and of physical

unity. Pevsner himself wrote that ‘in science one is engaged directly with

objective knowledge and logic. But in art this is not the case; instead, it is

a feeling of passion that moves an artist – it is love, it is poetry. Those in

science are involved with material things. Science foils poetry, for it is

deterministic’.

Pevsner’s

professorial role in the Vkhutemas became untenable after the promotion of this

manifesto. Moreover, the development of their new ideas in abstract art found

Pevsner and Gabo associated with activism on the grounds that they were guilty

of producing a type of art that had no basis in socialist realism. In both

practice and principal the Communist Party condemned the modern movement in art

and sought to impose the restoration of pictorial naturalism that had been

favoured by the old regime. Indeed, an exhibition of their work in the centre

of Moscow’s Tverskoi public garden in August 1920 resulted in accusations from

the new regime of ‘Capitalist art’, and despite inclusion in the 1922 Berlin

exhibition Pevsner later found his studio padlocked and his teaching

terminated. In choosing to maintain the integrity of their aesthetic ideals,

the brothers’ membership in the Central Soviet of Artists was withdrawn –

effectively depriving them of any possibility to earn a living from their art.

Both Pevsner and Gabo chose exile and possible penury over conformity to the

regime.

With

interest in pure Constructivism having waned in the Soviet Union by 1923

Pevsner sought inspiration in Berlin, where the enthusiasm for Constructivism

enabled him to begin his first construction after only nine months in the city.

Pevsner returned to France in October 1923 – the country that would later

become his adopted place of refuge and source of artistic emancipation. By June

the following year Pevsner was exhibiting his work with Gabo at the since

closed Galerie Percier in Paris. Pevsner’s contribution to Constructivist art

was recognised in the catalogue for the exhibition by the Polish art historian

and critic, Waldemar George, who introduced constructivism ideals as a symbolic

approach to life and cited the brothers as expert craftsmen in the expression

of this perspective through art. This sentiment is echoed by Read who claims

‘Pevsner’s technical skill is quite comparable to the skill of a Donatello or a

Rodin [since] what varies enormously in works of art is the quality of

intellectual vision’.

In

what Ruth Olsen describes as an ‘international constellation of artists’ we

find Pevsner and Gabo as significant co-founders in the Abstraction-Création,

art non-figuratif movement where they were regarded as the authority in

Constructivism. It was within this creatively vibrant environment that in 1932

their manifesto was partially reprinted and translated, in which their words

recalled how ‘to realise our creative life in terms of space and time: such is

the unique aim of creative art’. They continued by denouncing ‘volume as an

expression of space. Space can be as little measured by a volume as a liquid by

a linear measure. What can space be if not an impenetrable depth? Depth is the

unique form by which space can be expressed’. The translation concluded with

Pevsner’s and Gabo’s assertion that ‘the elements of art have their basis in a

dynamic rhythm’. Pevsner’s Constructivist rationale was

promoted further in 1937 following the publication of a one-off journal

entitled Circle. Co-edited by his brother, Gabo, this journal published

images of a number of Pevsner’s works, listed Pevsner on the title page, and

hailed both brothers as ‘the leading proponents of Constructivism’. Pevsner and a

group of his peers extended the Abstraction-Création movement in 1946 by

re-establishing the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles – a movement originally formed

in 1939 by Sonia Delaunay with the objective of promoting works of art

‘commonly called concrete art, non-figurative art or abstract art’. Pevsner

applied the values of the Salon and worked alongside Dealunay, Auguste Herbin,

Hans Arp, and Jean Gorin to mirror the purism of abstract art originally

established in Abstraction-Création. Yet despite his significant footing within

this art movement Pevsner remains an elusive figure in the historical record

concerning the development of Constructivism. Aside from supporting evidence of

his inclusion in exhibitions only basic biographical details about Pevsner

appear to have survived, although quite why is not entirely clear

considering his past prominence.

Indeed,

Pevsner exhibited his work widely during his lifetime. In 1926, for instance,

he exhibited in New York at the Little Review Gallery and at the International

Exhibition of Modern Art at the Brooklyn Museum with the Société Anonyme.

Pevsner’s and Gabo’s work reached new audiences when in 1927 their

constructions were commissioned as set pieces in the ballet La Chatte, which

was performed in Monte Carlo, London, and Ostend – with the programme clearly

acknowledging both brothers’ efforts. It was through the ballet’s central

figure in the décor that Pevsner completed his Cubist Constructivist period. In

the years that followed, Pevsner was represented in 1935 and 1936 in

exhibitions at Hartford, Connecticut, at the Chicago Arts Club, and in the

Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art. During 1937

Pevsner exhibited at the Kunsthalle in Basel with Constructivist and Dutch de

Stijl artists, and in the following year was part of a group of artists who

exhibited their work together at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Pevsner’s

work was also exhibited alongside contemporaries including Hans Arp, Henry

Moore, and Constantin Brâncuși at an exhibition in the former Guggenheim Jeune

Gallery in London whilst on a trip to visit Gabo just before the Second World

War. Pevsner’s success was rewarded when, in 1947, his first solo show opened

at the Galerie René Drouin. A celebration of Pevsner’s and Gabo’s significance

saw a full retrospective of their work at New York’s MoMA in 1948. Pevsner also

held exhibitions and installations in the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, with

the same museum organising a solo exhibition of his work in 1957. The

culmination of a lifetime’s work was recognised shortly before his death in

1962 when Pevsner represented France at the 1958 Venice Bienalle.

The

Guggenheim, MoMA and Tate Modern all hold major collections of Pevsner’s work.

Pevsner donated a selection of his work to The Centre Pompidou in Paris before

his death, leaving them as custodians of perhaps the widest range of his

sculpture, drawings, and paintings. After becoming a naturalised citizen of

France in May 1930, Pevsner was awarded in 1961 the Croix de Chevalier of the

Légion d’honneur (National Order of the Legion of Honour, knight class) for his

contribution to art. Despite the individual and collective artistic

achievements of both siblings Pevsner’s presence in the history and literature

of Constructivism remains sparse, with Gabo’s work eclipsing that of his elder

brother.

Provenance

Rabaudy collection, Paris

Private collection, Paris